|

Peter Westrich (aka Wichterich, Westerick, Westrick, Westerich, Wisterick) was born about 1846 (according to the 1905 Minnesota Census) or 1844 (according to his death record) in Germany. He is not found in public records prior to 1895 Minnesota Census.

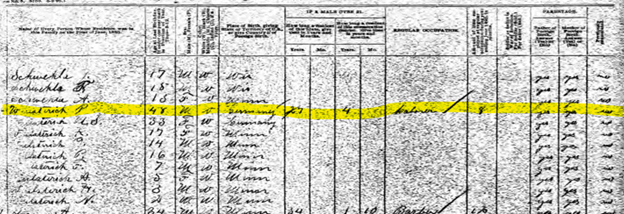

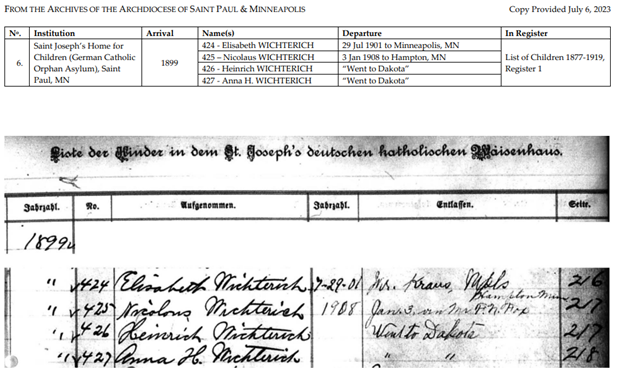

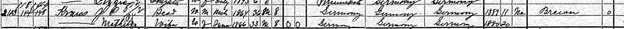

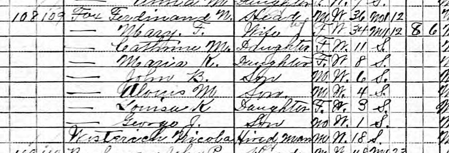

The 1895 census is a wealth of information (Figure 1). It shows Peter living in Faribault with a wife and seven children. Although born in Germany, he has been in Minnesota for 27 years and in Faribault for 4. He works as a laborer and had worked 8 months in the prior year. The city directory from the same year puts them on 1116 North Maple Street. His wife in 1895 is Mary who was born in Germany. However, she is only 33 years old. The oldest three children, Catherine (17), Peter George (16), and John (14) may not be her children. The four younger children are significantly younger – Frank (7), Anna (5), Heinrich (3), and Nicholas (1). The gap between John and Frank is also curious, given that all the other children are only a year or two apart. There are some potential records which are not complete enough to be conclusive, but form a tantalizing probable story. There is a marriage record from Rheinland, Germany, of a Peter Wichterich to Maria Catherina Schick, on 26 June 1866. Other records put the name of the older children’s mother as variously Mary Schuenke, Scheinke, or Schinke. Then there is a record of Peter Wichterich marrying Maria Konig 14 May 1884 in Rice County, Minnesota. These would match up well with the children’s known birthdates as well as ages for both Marias and would explain the gap between John and Frank. (Maria Konig would be 22 in 1884 if she is the Maria on the 1895 census, aged 33). Baptismal records for Nicholas and Heinrich give their mother as Emilia. However, Emilia and Maria Konig could very well be the same person. Another daughter, Elisabeth, was born in 1896. The eldest daughter, Catherine, married that same year, to William Bahe of Faribault. But something terrible affected the family between then and 1899. Because on 1 June 1899 the four youngest children were admitted into Saint Joseph’s Home for Children, also known as the German Catholic Orphan Asylum, in Saint Paul, Minnesota (Figures 2 and 3). There is no death record for Emilia/Maria/Mary. I cannot find a 1900 census record for Peter. Catherine was married but living with her in-laws with a baby in 1900. Peter George was working as a waiter in Fargo, North Dakota and living in a boarding house. John was in Hillsboro, North Dakota working as a day laborer, probably on the railroad. He was also living in a boarding house. One imagines that Emilia/Maria/Mary died in early 1899. No one in the immediate family was in a position to support the four small children. Leaving Peter with only the orphanage as an option. The one enigma here is Frank. He is too young in 1899 to be on his own – only 11. However, he does not appear in the orphanage records and does not appear in the 1900 census. Elisabeth left the orphanage first, on 29 July 1901. She was adopted by Jonathan (probably originally Johann) and Mathilde Krauss. The 1900 US Census provides a detailed picture of them. Both had been born in Germany, but they had been married in Minnesota in 1892. Jonathan had emigrated in 1889, at the age of 25. Since then he had become a naturalized citizen and was working at a brewery in Minneapolis. Mathilde had emigrated earlier, in 1880, aged only 13 or 14. They owned a house at 2123 Grant Street. They had no children in 1900 (Figure 4). The 1905 Minnesota Census finds Peter living at 821 8th Avenue South in Minneapolis. The census records him as being in Minneapolis for only the past two years. In the same building are John, now 24 and working as a baggageman for the railroad. John is married to Emma nee Kolb and they have a two-year-old son, George John. Also in the same building are Emma’s sister, Elizabeth, a laundress. Frank Westrich, now 17 is also at 821 8th Avenue South, employed as a typesetter. By then William Bahe and Catherine nee Westrich and little Arnold, had moved to 727 1st Avenue North in Faribault. William was working as a teamster. Peter George we do not find definitively. There is a 1905 Minnesota census record for a Peter Westrick working as a waiter in Duluth. However, the record has him as being 32 years old (birth year of 1873) and records his parents as being born in the United States. Although one wants this to be a link, it probably is not “our” Peter George. Nicholas (Nicolaus) is in the 1905 Minnesota Census at the orphanage (Figure 5). Heinrich and Anna are not listed. Their orphanage records (back to Figure 2) have the cryptic message “Went to Dakota” with no date. In 1905 Heinrich would have been only 11 and Anna 13. Anna’s individual record has the additional notes “went to work” and “adopted in Dakota”. Unlike Nicholas (see below) and Elisabeth (above), if Heinrich and Anna were adopted there is no record of the adoptive parents. On December 6, 1907 Peter died in Minneapolis. His death record gives the cause of death as septic pyemia (an infection of staphyloccus bacteria that causes pus-filled abscesses to form throughout the body; pyemia is treated today with antibiotics) and his occupation as laborer. His body was returned to Faribault for burial in Calvary Cemetery. On 8 January 1908, Nicholas was sent to Mr. F. N. Fox in Hampton, Minnesota (Figure 2). Hampton was, and is, a small farming town due south of Saint Paul, about 25-30 miles from the orphanage. It was probably a cold trip. On the 1910 US Census Nicholas Westerick is listed as a hired hand on the farm of Ferdinand N. Fox in Vermillion Township, Dakota County (Figure 6). The largest nearby town is Hampton. Heinrich has disappeared by 1910. I do not find him on the census. If he had been adopted he could have taken his adoptive parents’ name. Or he could have died. Child labor was notoriously dangerous at the beginning of the 20th century. By 1910 Catherine and William had welcomed a second child and had moved into a rented house at 817 Central Avenue in Faribault. William was now a baker for the Roell Bakery. Likewise John and Emma had welcomed a second child by 1910. They were still at 821 8th Avenue but now they had the building to themselves, and Emma’s sister Elizabeth. Peter George had married the widow Luella Fuller Whitman in 1907. He was working as a waiter at a café. They were living in a rented house at 806 Tenth Street South in Minneapolis - Peter George, Luella, Luella’s two children from her first marriage, and two boarders. Frank, according to his obituary, had left Minnesota for Colorado and then, by 1910, had arrived in Great Falls, Montana. He was single. Anna had gotten married in 1907 to Ferdinand Appl, and welcomed her first child in 1909. They were living with his mother, stepfather, and brother on a farm in Bogus Brook Township in Mille Lacs County, Minnesota. Ferdinand worked on the farm. Elisabeth had assumed the last name Krauss and was living at 1101 4th Avenue North in Minneapolis (Figure 7). The siblings stayed in touch with each other – we see them mentioned in the society pages as visiting each other and in wedding announcements for their children. And in the obituaries when they died. It would tie up many things if we could find details on Peter’s wife or wives. The mystery of why Catherine included Becker as a surname also remains a mystery. Could she have been adopted? Or married briefly before William? Or taken in by the Beckers for a time if tragedy took her mother in the early 1880s? We don’t know. While the orphanage records were a great help in tying things together they are also exceptionally brief. What happened to Heinrich? Where did Anna go when she “went to Dakota”? Was she really adopted or was it more a child for hire as Nicholas seems to have been? Plenty of "gold" left to find.

0 Comments

August 1862. The American Civil War had been raging for over a year. So far, it had seemed remote to the residents of Athens County, Ohio. But now news arrived that the rebels were on the move and rumor had it their goal was crossing the Ohio River and bringing the horrors of war to peaceful southern Ohio.

There was a rush of men to the recruiters. Defend the home! Repel the raiders! Included in these new recruits were three brothers from Athens County – Loren, William, and Eli Persons. They travelled to Camp Dennison near Cincinnati, Ohio where William and Loren were duly mustered into the Federal service with the 73rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Eli, however, volunteered to defend the river crossings. The process for joining the army during the Civil War, especially by 1862 when things had been “regularized”, was bureaucratic and time-consuming. Recruits would travel from their homes to local recruiters where they would be “enrolled” and then sent to a depot or “camp” where they would be examined by a physician, issued a uniform and equipment, and, at some point, they would “muster in” to service. It was this last step, where their names were placed on a muster roll, that their service usually officially began. Loren’s and William’s records show they enrolled August 22 at Athens and were mustered in on October 18 at Camp Dennison. Eli does not appear on a muster roll. There is a document in his service record, dated October 21, 1862, that says he was absent when the recruits were mustered in. In April 1863 Eli tried to obtain a discharge. There is a record signed by Dr. William Blackstone from May 1863 that notes Eli is incapable of service. It is a very sparse document, however, with no organization or discharge information completed. An affidavit from 1871 where he was applying for a disability (invalid, in the parlance of the day) pension, states he was given his uniform on or about 1 September 1862. Another affidavit, by Lieutenant John Kinney, who was acting as a recruiter for the 73rd Ohio in Athens in 1862, states that Eli was accepted for service August 31, 1862. Captain Higgins, in command of the recruits, asked for volunteers to repel the rebels – John Hunt Morgan and his cavalry was on the move! Eli raised his hand. He went with a detachment of volunteers to the Licking River in Kentucky. There, serving guard duty for two weeks continuously, he caught “cold which settled into his eyes”. Another affidavit, from 1875, notes that he was sent home, sick, and never went to a field hospital. In Athens he was treated by local doctors Moore and Blackstone. This is not surprising since the regiment, the 73rd Ohio, was in service with the Army of the Potomac, at that time licking its wounds from the Second Battle of Manassas in camp in front of Washington, D. C. The regimental surgeon was likely quite busy and hundreds of miles away. Eli’s “cold”, in the words of Doctor Moore, left him totally blind in one eye and virtually blind in the other. Congress had passed the first Invalid Pension Act on July 14, 1862, granting a monthly payment of $8 for soldiers suffering “total disability” for the performance of manual labor. That is, the Act was passed before Eli walked off his farm to help repel the rebel invasion. An updated Act of June 6, 1866, expanded this to award those incapacitated for the performance of “any manual labor.” Being totally or virtually blind, one would think, qualified Eli for a pension under either Act. But Eli did not apply until November 1871. One wonders how he and wife Susan, and their four children (all under age 10 when he returned from Kentucky) got by. On November 13, 1871, Eli applied for an invalid pension. He acquired affidavits from Dr. Mordecai Moore who had treated him upon his return to Athens, Dr. Eusebius B. Waterman and Dr. Sebastian Rehm, who both treated Eli in the spring of 1863. He also included a plaintive report: “there is no other Doctors whose affidavit I can obtain. Doctor Stuart who treated my Eyes a Short time Is I Believe Still living. But I can not learn his address. Dr. Cornell of Chester, Ohio who treated me a Short time, has become a habitual drunkard and claims that he cannot Remember of treating my Eyes. Dr. Ferrell of Cincinnati, Ohio is Dead. He also having treated my Eyes for Some time.” Eli included an examination performed January 15, 1872 which confirmed he was still blind and would remain so – total and permanent disability. The above-mentioned Lieutenant Kinney’s affidavit was included. Finally, included in the application were affidavits from Alonzo Buck and Alpheus C. McGrath recounting Eli’s service story - he had enlisted, volunteered to fight Morgan, become sick leading to blindness while on duty. Also in his record is a note from the War Department to the Pension Office (part of the validation process) with the ominous statement, “The name of Eli Persons does not appear on rolls Co “K” 73rd Regt Ohio Vols on file in this office.” Nothing more. Next in the record is a letter from Eli’s attorney, W. W. McCormick, dated October 10, 1872, almost a full year after the application, asking for the status. A note on the back, apparently by a clerk in the Pension Office, states the application had been referred to General Foster on August 29. My, how the wheels of bureaucracy turn! Patience, however, was eventually rewarded. Although there are no documents in the record in 1873 and 1874 one can imagine a bureaucratic exchange of letters. Finally, Eli was granted a pension under the Special Act No. 28 of 1875, in the amount of $24 per month starting February 11, 1875. This amount was rapidly increased over the next year, to $31.25, then $50 and finally, on June 17, 1878, to $72 per month. In May 1904 this was increased again, to $100 per month. When Eli moved, in 1886, to Minnesota, his pension was switched to the Milwaukee office and the money continued to arrive. He and Susan settled into life in the town of Long Prairie, near where their children had taken up their trades - Sam and Sylvester in agriculture and Elizabeth was managing a growing family beside her blacksmith husband. However, on the 4th of July 1905, a challenge was made. Henry Baugh, a plasterer and (later) mason, filed a letter with the Chief of the Pension Bureau reporting “a large pension being drawn by fraudulent means.” Baugh had moved with his family to Minnesota from Indiana when he was 5. The 1875 Minnesota Census shows him living with his parents in Gordon Township, Todd County. He and his second wife, Charlotte, had moved to Long Prairie at the beginning of 1905 (according to the 1905 Minnesota Census). The 1910 US Census showed them living only a couple houses away from Susan. Henry’s source of information is lost to history. But, in a letter to the Bureau of Pensions, dated August 15, 1905, he says “I do not believe he [Eli] was ever mustered into the service”. He names three witnesses – one in Todd County and two more still in Athens County, Ohio. Curiously Henry states the pension amount to be $72; clearly not knowing about the 1904 increase. The first line of the last paragraph is also interesting – “Please keep my name out of it as I cannot swear to anything.” There is a response from the Milwaukee Pension agent to the Commissioner in Washington, D.C., dated August 29, 1905, where Eli’s particulars are included. There is a note in Eli’s file of Henry’s protest. However, the Commissioner replied to Henry on September 13, 1905: “…you are advised that the papers in this claim show that Mr. Persons was originally granted a pension by a Special Act of Congress, and that the facts relative to the soldier’s service were known to the Senate Committee on Pensions, where the bill of his relief originated.” Eli’s pension was not interrupted. On February 20, 1908, Eli died. Susan filed for a widow’s pension the next month. Only to be rejected. A clerk’s slip in the record, dated May 12, 1908, directs the Western Division to send a letter rejecting Susan’s claim. A note on the outer jacket of Eli’s pension record states the rejection was because the “soldier never mustered in service.” The reasoning for rejection was that because Eli was added to the pension rolls by Special Act and not regularly, she had no “title” to widow’s benefits, as they were only available to those who had been “mustered in.” There is no communication in the file past this. Apparently, Susan did not receive any benefit. Perhaps Henry Baugh grinned from across the street at her misfortune. Thank you to Dan Persons for the discharge documents. Brothers Heinrich and Herman Schroeder emigrated in 1871 from Hannover to Shakopee, Scott County, Minnesota. They were both single when they arrived. IN Shakopee the brothers started a brick manufacturing business. In 1872 Heinrich married Sophia Reinke. Three years later Herman married Maria Reinke. Both wives were also Hannover-born.

The 1880 census has the two brothers living on Bluff Street in Shakopee, in adjacent houses. Heinrich is listed as having six boarders and a servant in his house with all of the boarders working at the brickyard. About 1883 Heinrich packed up his family and moved north, to Long Prairie, Todd County, Minnesota. It is from Heinrich's branch that I am descended, making Herman my great-great grand uncle. Herman continued the brickyard and branched out into fuel, one assumes because the brickyard consumed plenty of fuel in its kilns. Herman and Maria had five children, all of whom were involved in the business. The 1900 census gives us the next snapshot. Herman has Maria and all five children in the house of Bluff Street, plus two brickyard employees as boarders. The oldest son, Henry Conrad, is employed as an accountant. The oldest daughter, Amelia, apparently helping Maria to run the busy household. The youngest three were in school. Ten years later, Henry Conrad had moved out (he got married in 1903) but the other children were all in the house. Adolph is listed as a teacher in the "Common School". There is still one brickyard worker boarding. The girls - Amelia, age 29, Anna, age 23, and Lena, age 20 - all all at home and have no occupation listed. By 1920, the four children are still living with Herman and Maria on Bluff Street. But now all of them are listed as being employed. Amelia is now the bookkeeper for the brickyard and Adolph is in sales. Anna is teaching school and Lena is a nurse, working at the hospital. Herman died in 1922 and Lena in 1926, making a much reduced household by the 1930 census. Adolph had gotten married in 1923 and moved out of the Bluff Street house. He took over the brickyard on Herman's death. Anna was still teaching but Amelia was no longer listed as being employed. Maria died in 1932. After the reunion last summer and the publication of Defined by Us (for the Parsons/Persons/Schroeder line) I took a few months off. I am slowly starting to research more. I have been trying to get the Bahe/Tallard/Seesz line in a place where I can similarly publish an initial narrative, and have made progress, but it is not yet ready.

I thought it appropriate to include all of you in the journey, as it is a combined voyage, so have started this blog and will try to update it as I do more research. As always, if you have something, anything, to share, it is both much appreciated and will be added to the narrative. Comments are encouraged, as long as we all follow the simple rules of being courteous and respectful. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed